You cannot book specific historic rooms. After your reservation is made, you can reference the room number with the name of the room to view the history on these rooms. Sorry for the inconvenience.

This historic suite is as named after the mover and shaker of his generation. You will spend the night in the room where the man himself slept, Buffalo Bill. This is the largest suite in the Irma. The room is located on the second floor, this suite was two rooms separated by the bathroom and a second door, lavish historic furnishings like a clawfoot tube, extraordinary views of downtown Cody, stained windows, a king size bed in a private bedroom, as well as a full seating area in the living room, accommodating two guests. Leaving this room, the premier choice in all of the Yellowstone National Park area.

As anyone driving through Cody can see, this little town is proud of its very own hero, Buffalo Bill Cody. In his later years he devoted much of his time and money to Cody’s development; adding his own special spark of glamour and excitement. We have created the Buffalo Bill Room in the Irma Hotel so that you, too, might absorb some of the magic surrounding this man in the hotel he built and named after his youngest daughter Irma.

William F. Cody was born in LeClair, Iowa on Feb. 26, 1846 to Mary and Isaac Cody. He was the youngest in the family of five sisters and one brother. When he was seven, the family moved to Ft. Leavenworth, Kanas where his father staked a claim and became an Indian trader. By the time young Bill Cody was eleven both his father and older brother had died and it was left to him to support his mother and sisters.

He had been working for the firm of Russell, Majors and Waddell herding cattle for two years and was promoted to the job of dispatcher for a wagon master with a bull train bound for Laramie. He spent that first winter as a trapper around Laramie. The next summer he joined the gold rush to the Pike’s Peak country near Denver.

By 1860 California was demanding a fast, reliable mail system. The government recruited the firm of Russell, Majors and Waddell to find a mail route to California. Soon 190 relay stations were built along the trail to California, and the Pony Express was born. Four hundred of the fastest and best horses were bought and riders were selected on the basis of endurance, reliability and small stature.

Bill Cody was hired as a Pony Express rider at the age of 14. In spite of his youth he had proved his worth and was a valuable asset.

He rode his 25 – 30-mile route without incident until one day he was thrust into the public imagination by making a ride that was never again equaled in the history of the Pony Express. His relay stations had been burned down by Indians and it was up to him to get the mail through, in spite of exhausted horses and adverse conditions. He rode some 328 miles in less than 22 hours.

The Pony Express, incredible and romantic as it was, was short-lived and was soon replaced by the transcontinental telegraph lines. The Pony Express had died but Bill Cody was just beginning to mature. For the next three years he added much to his knowledge of the plains and became a famed and noted frontiersman, counting among his close friends such people as Wild Bill Hickok and Kit Carson.

When the Civil War exploded in 1864 Bill was 18. He enlisted in the Seventh Kansas Volunteers and served for 19 months. It was during this time that he met and married Louisa Frederici. There are stories of Cody gallantly rescuing her from a runaway horse and falling in love with her at first sight.

The couple had three daughters – Alta, Orra, and Irma as well as one son, Kit Carson Cody. They were all to precede him in death except Irma who died only one year after his death.

Soon after his marriage, Cody returned to Kansas and the style of life he loved. This time going to work with Bill Hickok as a civilian scout between Ft. Ellsworth and Ft. Fletcher. His wife Louisa had become disenchanted with her husband’s wild and woolly career and tried again and again to make him settle down to some secure city job. But Bill wasn’t cut out to be a city man and this led to a troubled marriage and many long separations.

In 1867 at age 21, Cody went to work for the Kansas Pacific Railroad at the unheard-of salary of $500 a month. He had the dubious job of killing 12 buffalo a day in order to feed the large construction crews. Needless to say, this made him fairly unpopular with the Indians who depended on the buffalo for their very existence. Unlike the Native Americans, the white man wasted much of the buffalo and used only the prime cuts of meat.

We can imagine that he spent a good deal of his time avoiding potshots from the unhappy Indians. According to Cody, he killed some 6,570 buffalo in the 18 months that he was employed by the Kansas Pacific. Right or wrong, this is how he got the nickname “Buffalo Bill,” a name that stayed with him from that time on.

Bill had gained a good deal of attention in eastern newspapers because of his colorful lifestyle. He had the typical look of the dashing frontiersmen that easterners dreamed about, wearing his thick brown hair shoulder-length and sporting a mustache and goatee.

In 1868, Cody returned to his job as a government scout, this time stationed at Ft. Larned. He performed remarkable rides between forts, once covering 355 miles in 58 hours of day and night riding. He returned to guiding national and international figures, like the Grand Duke Alexis of Russia, through the west.

Bill also served as Chief Scout for the Fifth Cavalry in many of their expeditions against the Indians. In the Battle of Summit Springs, he lived up to his romantic, chivalrous reputation when he rescued a lady held captive by the Indians.

Cody had proven himself as a valuable frontiersman and was in great demand as a guide for such famous generals as Custer, Sheridan, and Miles. During this time, he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for bravery.

Before Bill ever dreamed of becoming a showman, there were many who were already making money on his charismatic personality. Novelists were churning out “dime” novels about the famed Buffalo Bill and his daring exploits. One of these, Ned Buntline, wrote a book called “Buffalo Bill: King of the Border Men.” A stage play based on the book was playing to large sellout audiences in New York where the wild West was all the rage.

On a trip to New York, Cody went to see the play, he was asked to stand and take a bow, and it was an overwhelming hit. This gave the manager an idea and when the show was over, he asked Cody if he might consider moving to New York and play himself on stage.

Cody had just been elected to the Nebraska State Senate but a few months later he decided to give acting a whirl so he resigned from the Senate and headed for New York. No one knows exactly why he decided to make the big change but perhaps he thought life in New York might please his wife Louisa or perhaps he simply liked the idea of a new adventure.

Cody’s first attempt on stage was an immediate hit. He would ad lib the lines and use the names of celebrities and friends in the audience. The crowds went wild and loved every minute of it. He had a natural charm and people knew that this was no charlatan but the real thing.

He often had some other famous scout such as Texas Jack or Wild Bill Hickok along with him as well as Indians and even wild animals. For the next few years Bill Cody played the winter season in the East and then in the summer he would return to the West, where the air was clean and there was plenty of room to move.

In the spring of 1876, after the death of his son Kit, Cody went West to aid in General Crook’s campaign against the Sioux. When he reached Cheyenne, he received word of Custer’s death at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. After this sad news, Cody was off to avenge his fallen comrade. It is said that he is the man who killed the famous warrior Yellow Hand although no one knows for sure. Again, he was appointed “Chief of Scouts” and tracked Indians all that summer.

Upon his return to the East that fall, he was given a hero’s welcome by the press and soon opened in a new play called “The Red Right Hand: Or Buffalo Bill’s First Scalp for Custer.” Buffalo Bill, newly returned from the Wild West, was once again a smash hit.

The next summer he and a Nebraskan, Captain Frank North, bought a ranch near North Platte called the Scout’s Rest Ranch. Once again, he was embarked on a new adventure. He learned the life of a cowboy and spent much of his time on the range with the hired hands. His wife Louisa and their daughters came out from New York and moved into their beautiful new ranch home. Bill Cody couldn’t ever sit still long though, and soon he was back entertaining devoted crowds during the winter season.

Cody was a dreamer and knew that soon the old West would be tamed and folks would want to know what it was once like. He devoted as much time as he could to recording his impressions and writing about this unique style of life. There are many books attributed to him, and it is hard to imagine when he was able to find the time.

By 1883 Cody had had enough of stage shows. They were extremely popular and tremendously lucrative but Bill had a new idea. He was intrigued by the skills of the common cowboy and the stage was too confining to really depict any of this.

He envisioned a large outdoor show with horses and cattle, Indian raids, shootouts, and bucking horses. So that year he enlisted several partners and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show was born. The show was the first of its kind, and was a forerunner of modem day rodeos. He hired cowboys, rough riders, Indians, sharpshooters, and musicians. He rounded up horses, cattle, buffalo, bears, and mountain sheep. With this odd and assorted entourage, he spent the next three years touring the U.S.

Buffalo Bill insisted on authenticity and he got it. His rough riders would rope some wild-eyed horse, cinch on a saddle, then climb aboard and hope for the best. One of the highlights in the show was the famous rifle markswoman, Annie Oakley, dubbed “Little Miss Sure Shot” by one of her admirers. There was also fancy roping, Indian dances, a Buffalo hunt, sharp shooting, and trick riding. Stagecoaches and covered wagons were dramatized and when the dust cleared Buffalo Bill would be seen sitting bare headed, on his beautiful white horse while the Star-Spangled Banner played in the background.

The crowds went wild and the Wild West Show was the biggest success ever. People loved him and he loved people. He was a “soft touch” and was always ready to help someone out when they were in need. His managers would tear their hair out but he could never say “no” to someone less fortunate than he.

Buffalo Bill took his troupe to Europe for Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee of 1887 as part of the large American Exposition honoring the event. Just before he left, the famous showman was notified that he had been appointed a Colonel in the Nebraska National Guard by Governor Thayer. With his new title of Colonel, Buffalo Bill and his show set sail on a chartered ship.

According to the newspapers there were “83 cowboys, 38 roustabouts, 97 Indians, 180 horses, 18 buffalo, 10 mules, 10 elk, 5 wild Texas steers, 4 donkeys, and 2 deer. They were an unqualified success in England. Royalty and bigwigs, as well as thousands of commoners, attended every performance. Titled or commoner, all the English loved him.”

Once, Buffalo Bill drove a stagecoach around the arena while the Prince of Wales rode “shotgun”. Seated inside was the King of Belgium, the King of Saxony, the King of Denmark and the King of Greece. As they drove around the admiring ringside, his royal highness, the Prince of Wales said, “It isn’t often that you hold as good a hand as this-four kings-is it Colonel Cody?” The Colonel replied, “No your highness, although I have held them occasionally. However,” after a pause, “this is the first time I ever held four kings as well as a royal joker.” That night they had champagne.

The Wild West Show and the Congress of Rough Riders of the World toured England all the next winter, returning to the states in May 1888. After a short U.S. tour, they packed up again and spent two years touring continental Europe, once performing for the Pope at the Vatican. The Wild West Show and Buffalo Bill were loved everywhere they went. Colonel Cody soon became the most well-known American in the world as a brilliant ambassador of good will.

In 1890, Indian troubles flared up once again on the home front. Buffalo Bill returned shortly after the massacre at Wounded Knee hoping to cool things down without any more bloodshed. General Miles asked him to talk to Chief Sitting Bull since Bill Cody was one of the few white men that Sitting Bull trusted. Sitting Bull had at one time traveled with Cody as part of the Wild West Show. Sitting Bull was killed before Cody could reach him.

By 1893, the Wild West Show had grown so big that the mess hall fed 640 people. They toured Europe again but the season was short and the expenses were outrageous. This time the tour was a success in every way except financially. The Show returned to the states to perform for the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893. There they played to capacity crowds without the expense of being continually on the move. That summer proved to be the most financially rewarding season in the history of the show.

Colonel Cody had purchased a lavish hotel in Sheridan, Wyoming and in 1894 while visiting in Sheridan he heard glowing stories of the beautiful Big Horn Basin area just over the mountain and west of Sheridan. He was introduced to a Sheridan man by the name of George T. Beck who had hopes of introducing irrigation into the Big Horn Basin country and starting a new town.

Cody had seen the area years before, as a guide for a geological expedition, and had been impressed even then. He was a dreamer and could envision a glorious future for that part of the country and soon became enthusiastic about the project. Col. Cody approached Beck and his partner Horace C. Alger and, in the fall of 1894, became a third partner in the Shoshone Land and Irrigation Co.

Beck and Alger knew that Cody would be a valuable partner. He was very influential throughout the U.S. and would be able to raise money and interest for the project. Sure, enough the next winter he went to Buffalo, New York, where his enthusiasm about the project invoked the interest of four wealthy men, Monte Gerrans, Nate Salsbury, Bronson Rumsey and George Bleistein. The next year these four men came out to look over the area. They each put up $5,000 and became directors of the Shoshone Land and Irrigation Co.

Everywhere he traveled with his Wild West Show Cody told people about the project and its bright hopes for the future. By 1897, the canal was completed and the little town had been christened “Cody” in honor of the man who had been instrumental in its development. Col. Cody frequently visited the little town and often brought his famous friends along with him. He entertained everyone royally and soon became a trusted friend of the pioneers who had come into the area. The Colonel was now the proud owner of three cattle ranches around his town, one of which was the beautiful TE Ranch on the Southfork where he was to spend much of his time in the years to come.

Cody had faith in the little town, so in 1902 he began the construction of his beautiful Irma Hotel, named after his only surviving daughter. All the materials and ornate furnishings for the hotel had to be brought in by wagon train. In no way could he hope to recoup his investment in this endeavor, but he could show the confidence he felt that someday the Cody country would prosper.

The Wild West Show was still going great guns and Bailey of the Barnum and Bailey Circus had become his partner in 1900. In 1902 they toured Europe again and Col. Cody continued pouring money into his little town. He built his beautiful hunting lodge, Pahaska Tepee, near the east gate of Yellowstone. “Pahaska” was Cody’s Indian name meaning “Long Hair.”

He also built two other inns along the road to Yellowstone Park. Col. Cody was also instrumental in getting a railroad spur line into the town from Montana.

Buffalo Bill Cody was a great friend of President Theodore Roosevelt and through this connection he was able to get the tallest dam in the world constructed on the Shoshone River just west of Cody. Col. Cody’s contributions to the town he loved were uncountable. He poured his heart and soul into the area along with all of his money. Until his dying day he remained a “soft touch” and would never hesitate to help someone out when help was needed.

In 1916, the year before he died, he led a group of friends to the top of Cedar Mountain and it was here, overlooking the town of Cody, that he expressed his wish to be buried. On Jan. 10, 1917 Col. William F. Cody died in Denver, Colorado. He was buried there atop Lookout Mountain far from the mountain and town that he loved, despite his wishes to be buried near Cody.

Buffalo Bill Cody was truly an exceptional individual. It would be difficult to find any person in history who excelled in more endeavors or who lived a more colorful life.

There have been attempts to discredit him, by people who just didn’t know or appreciate the history of his era, or by those who could not believe it could all be true. It is truly amazing to know that he was all of these characters in one lifetime Pony Express rider, Indian scout pioneer, statesman, and the world’s greatest showman.

Let the world know that his townsmen in Cody, Wyoming honor and revere his memory.

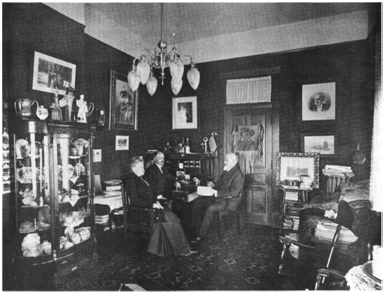

During the early years of the town of Cody, Colonel Cody returned here frequently from his Wild West Show tours. His generosity and love of people as well as his flair for entertaining brought people from far and near when he was in town. He stayed in his suites in the Irma Hotel, here pictured with daughter Arta and her husband, or at his TE Ranch on the South Fork of the Shoshone River.

2026 © Buffalo Bill's Irma Hotel • Cody, Wyoming