You cannot book specific historic rooms. After your reservation is made, you can reference the room number with the name of the room to view the history on these rooms. Sorry for the inconvenience.

This historic suite is as named after the amazing author and journalist, who was as witty and adventurous as her writings. One of the greatest girls in the Yellowstone area at the time. This room is located on the second floor, this suite offers two areas, a sitting area with a table, lavish historic furnishings, and views of the haunted Irma room. The suite has two Queen size beds, accommodating four guests

Caroline Lockhart led a life that would make a book as exciting and colorful as those she wrote. She was truly one of the first women to whom one could say, “you’ve come a long way baby!”

Miss Lockhart’s novels and her columns as editor of the Cody Enterprise rang with sharp wit, humor, and bright hopes for the underdog. The great American writer and publisher H.L. Mencken once called her “one of the four best humorists in America.” It is in honor of this colorful and courageous woman that we name The Caroline Lockhart room of the Irma Hotel.

Caroline Lockhart was born in 1871 at Eagle Rock, Illinois. and grew up on her father’s ranch near Eskridge, Kansas. She attended Bethany College in Topeka, Kansas. and the Moravian Seminary in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. After a brief career on the stage she went to work for the Boston Post. She was a novelty as Boston’s first woman newspaper reporter, matching the pace set by her contemporary, the famous Nellie Bly of the New York World.

She quickly distinguished herself as a feature writer under the pen name of “Suzette.” Feature assignments covered by “Suzette” included such things as walking around on the bottom of Boston Harbor for a half hour in early day diving gear, entering a circus cage with a lion who had killed his trainer the day before, and testing out the Boston Fire Department’s first fire nets by jumping out of a fourth story hotel window.

Lockhart was able to close down an illicit home for wayward women after she had stayed there in disguise for several days investigating the atrocities. The “home” advertised to help women with drinking problems and give them the cure, but in actuality merely capitalized on them by putting them to work on mangles doing laundry for Boston hotels.

Miss Lockhart believed one had to experience a way of life to write about it. She once joined a circus and vaudeville act and traveled with them long enough to be able to tell about it. She also went to work cooking for Chief Bacon Rind of the Osage Indians. Apparently, when they got rich overnight with royalties from their oil lands no one could get in for a story. But persistent Caroline wouldn’t take no for an answer. When her story about them came out in the Denver Post the whole issue sold out in less than 30 minutes.

Caroline was a close friend of Anna Jarvis, the woman who has been given the credit for starting Mother’s Day. Miss Jarvis came to Caroline with the plan of making Mother’s Day a nationwide celebration. It was with Caroline’s help and through her journalistic efforts that the whole thing got started and Miss Jarvis always held that it was really Caroline who deserved the credit.

Following an interview with William F. (Buffalo Bill) Cody, who was on an eastern tour with his show, she decided to move to his hometown of Cody, Wyoming. This was in 1904. For the first few years in Cody she stuck to writing magazine stories and soaking up the benefits of living in the west. She wrote a series of “rip-snorting, belly tickling” stories about Cody that appeared in the Stockgrower magazine.

In 1919 she purchased and edited the Cody Enterprise, Cody’s weekly newspaper. Her wit and crusading leadership soon won fame for her and her newspaper. Paul Eldridge, a professor of English at the University of Nevada, worked for Miss Lockhart about this time. He recalls her daily arrival at work this way:

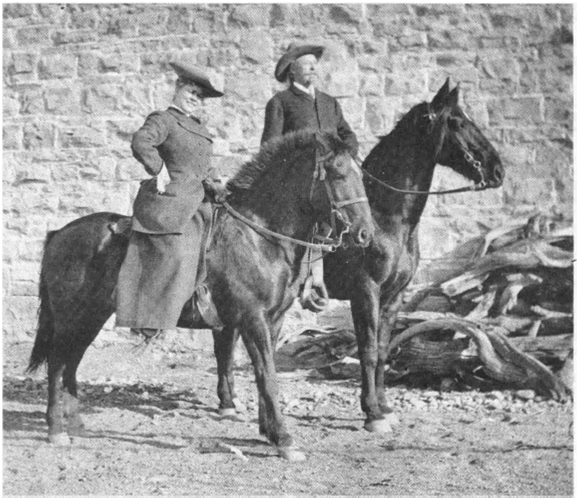

“She rode her horse … (always a buckskin for she loved that color and would own no other) dismounting, tying him to the hitching post, clumping and jingling in boots and spurs, wearing a divided skirt and a $20 Stetson, a smile on her face as she meditated mischief on her opposition or inquired as to their latest attack.” She worked hard against prohibition’s dry laws and reformers in her column “As Seen from the Water Wagon” and attacked “game hogs” and those who wished to change the nature of the old west. During her editorship her slogan was “Everybody reads the Enterprise, even if they have to borrow it!”

It was Caroline Lockhart who founded and first directed the Cody Stampede, Cody’s two-day Fourth of July celebration. She would head the parade in those early days on her favorite horse and was usually accompanied by some prominent person such as the governor. She entertained the Indians from the Crow Reservation who would come down for the big event, at her own home. After they would leave, she would invariably find her supply of French perfume somewhat depleted. She was a personal friend of Chief Plenty Coups and was responsible for a beautiful headstone erected at his grave at the time of his death.

While she was in Cody she wrote and published most of her novels. Her first successful novel, “Me Smith” was written in 1911. Her second book was “The Lady Doc” published in 1912. “It made me infamous,” she once said, “some people saw themselves in the characters.” The book seemed to be based on Cody and the people there. It wasn’t exactly complimentary in what it said about certain people around town.

Caroline Lockhart, like Will James, relied on first hand observation for her material. Other books included “Full of the Moon,” “Man from Bitter Roots,” “The Fighting Shepherdess,” and “The Dude Wrangler.” Her last novel, “The Old West and the New” was written in 1933. In this book she explored the changes that the 20th century had forced on its colorful old-timers.

In a “twenty years after” sequel, the characters in the first part of the book reappear in the disguise of dude wranglers, filling station operators and prohibition agents, instead of cowboys and cattle rustlers.

Caroline was a great traveler and journeyed to many parts of the world. Once, while in Nicaragua, the hotel in which she was staying burned to the ground. Luckily, she was out at the time but her only manuscript of the novel she had just finished had gone up in flames. No stopping Caroline though; she simply sat down and rewrote the whole thing.

In 1924 Miss Lockhart sold the Cody Enterprise and followed her pioneering instincts by buying a beautiful ranch in the very isolated Dryhead country between here and the Crow Indian Reservation. She ran a tight outfit with top cattle and would often help the hired hands with the work of rounding up, branding, and shipping her stock. She maintained her home in Cody, however, and between seasons when work was slack, she would return to her typewriter here in town. She died here at W.R. Coe Memorial Hospital in 1962 at the age of 91.

Caroline Lockhart was truly a dynamic pioneer woman and lived a vigorous life that sparkled with all the action and adventure of the western novels she wrote.

Caroline Lockhart came to Cody in 1904 at the age of 33. Her move to the West from Boston came after she had written a newspaper interview with Buffalo Bill Cody. She believed in actually experiencing the things she wrote about which led her into many adventures and brought her a great deal of attention. She bought the Cody Enterprise and edited it from 1919 to 1924.

2025 © Buffalo Bill's Irma Hotel • Cody, Wyoming